3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, R.A., Burma Auxiliary Force

Formed in 1941 as part of the 1st Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, R.A., B.A.F., the 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Battery formed part of the Rangoon Garrison until 7th March 1942 when the British evacuated the city. It was equipped with eight 40mm Bofors light antiaircraft guns. The Battery joined the fighting retreat of British forces in Burma and on reaching India in May 1942 was sent to Mhow, in the central state of Madhya Pradesh.

As the threat of war with Japan grew, in 1941 a new Auxiliary Force unit was created for air defence. This was the 1st Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery, Burma Auxiliary Force. It was formed with two batteries:

- 1st Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery with eight 3-inch guns

- 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Battery with eight 40mm Bofors guns.

However, the guns were not available immediately and training went ahead without them. Eventually, the guns arrived just before the outbreak of war with Japan. Both the heavy and light guns were stationed in and around Rangoon, with a detachment at the oil refineries at Syriam.

On 23rd December 1941, Rangoon was raided by the Japanese and again on 25th December. The 1st Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment claimed three aircraft shot down but two 3.7-inch and one 40mm Bofors guns were damaged. Having disembarked at Rangoon on 31st December 1941, also now serving in Burma was the 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, Indian Artillery, and in January 1942 this battery sent its 'C' Troop with its four guns to Moulmein. During the withdrawal from Moulmein, on 31st January, the personnel of the troop managed to escape across the Salween River to Martaban but the guns had to be destroyed. Having hastily reorganised, 'C' Troop of the 3rd Indian L.A.A. Battery then took over four guns of its Burma namesake on 17th February 1942, at Mingaladon. Along with the remainder of the garrison, both the 1st Heavy and 3rd Light A.A. Batteries of the B.A.F. left Rangoon on 7th March 1942, destroying the static heavy anti-aircraft gun positions before leaving. The surviving heavy anti-aircraft guns were sent to Hlegu along with detachments of the 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, B.A.F. However, the way north from Rangoon was blocked by the Japanese at Taukkyan and a fierce battle ensued to open the road for the Rangoon garrison. In support of the troops was every anti-aircraft gun in Burma. Within a two square mile area were heavy and light guns from the 1st Heavy Regiment, B.A.F., the 8th Heavy Battery, R.A, the 8th Heavy Battery, Indian Artillery and the 3rd Light Battery, I.A. After several unsuccessful attempts to clear the Japanese, on the morning of 8th March it was found that the Japanese had pulled out, leaving the road clear.

In April 1942, most of the surviving anti-aircraft guns available to the British were concentrated around the vital Irrawaddy bridges at Mandalay. The 1st Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery destroyed its 3.7inch guns at Shwebo, being unable to move the guns any further. Throughout the campaign, the 1st Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, B.A.F. claimed 19 Japanese aircraft destroyed of which four were claimed by the 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, B.A.F.

The photographs included here are from the collection of Major Arthur Cockle. Major Cockle was working as a civil servant in Burma before the war and was called into the B.A.F. He served with the "3rd Ack-Ack" (slang for the 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, B.A.F.) as a Captain. When Rangoon was evacuated, he gathered what was left of the remaining troops and led them on foot from the city on the trek to India. At one point on the journey, they reached a place where a road was being constructed. Captain Cockle would not allow any of his men to use it nor the transport provided as the road was so treacherous. Apparently when they built the road, the materials were so poor, that any amount of precipitation caused it to act like a skid pan. The army lost endless vehicles, new and old, "over the edge" of this newly constructed road. In fact it was so poor that walking along it was just as bad. Captain Cockle recalled that “all the men deserved medals just for getting from here to there using that road!”

Following disbandment of the Battery in India, Captain Cockle was initially transferred to serve with the Indian artillery. Many of the surviving men joined the Burma Intelligence Corps. Subsequently, Captain Cockle was asked to volunteer for Special Forces. As a member of the Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.), he played a significant role in organising the hill tribes to fight against the Japanese. He was awarded the Military Cross and towards the end of the war was promoted to Major.

I am very grateful to Major Cockle for permission to publish his story and photographs.

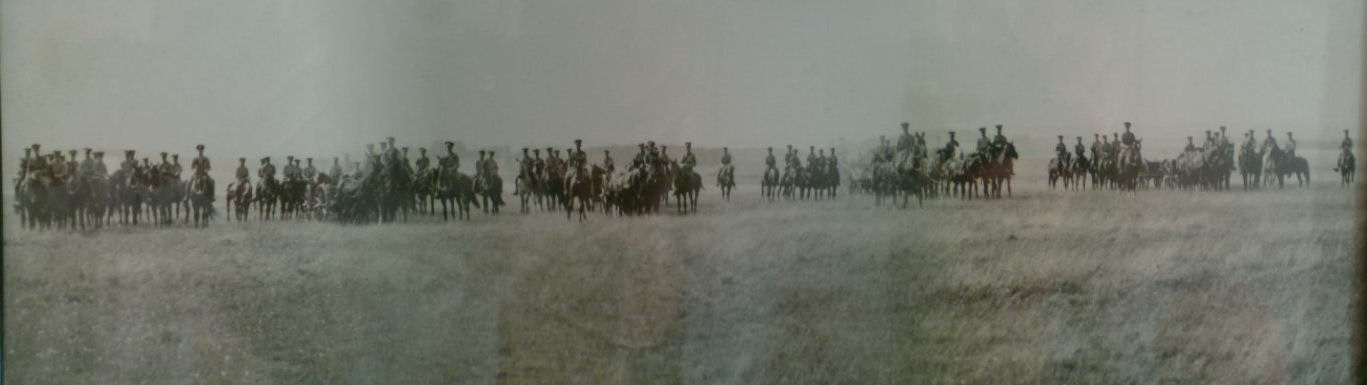

1. Burma Auxiliary Force on manoeuvres with what appear to be field guns and limbers - date unknown but appears to have be taken before the Japanese invasion.

Click image to open full size in new window

2. Officers of the Burma Auxiliary Force - date unknown but appears to have be taken before the Japanese invasion.

Click image to open full size in new window

3. Officers and men of the Burma Auxiliary Force - date unknown but appears to have be taken before the Japanese invasion

Click image to open full size in new window

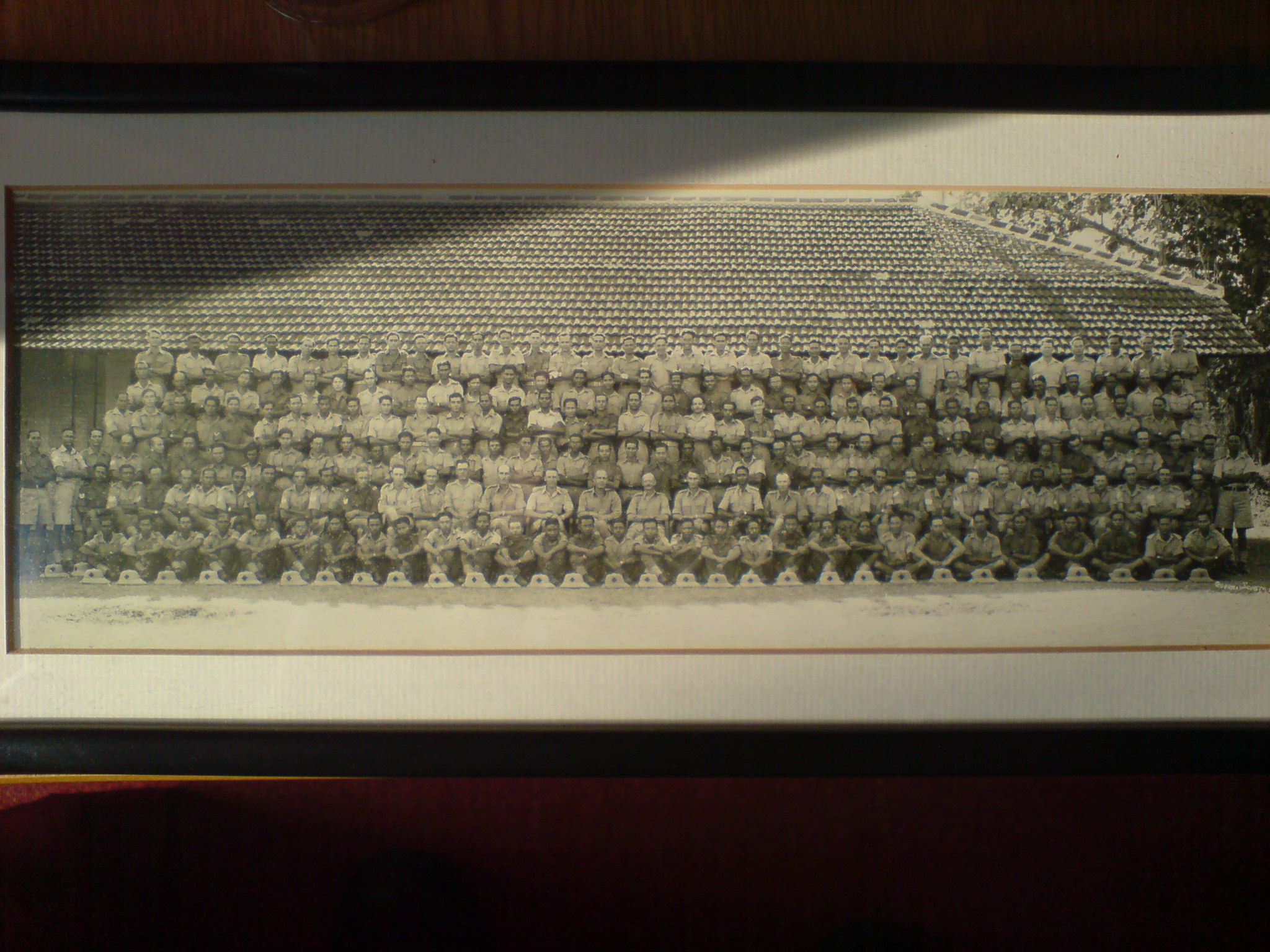

4. Officers and men of the 1st Heavy Anti-Aircraft and the 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Batteries, 1st Heavy Antiaircraft Regiment, R.A., Burma Auxiliary Force - date assumed to be mid/late 1941, Rangoon.

Click image to open full size in new window

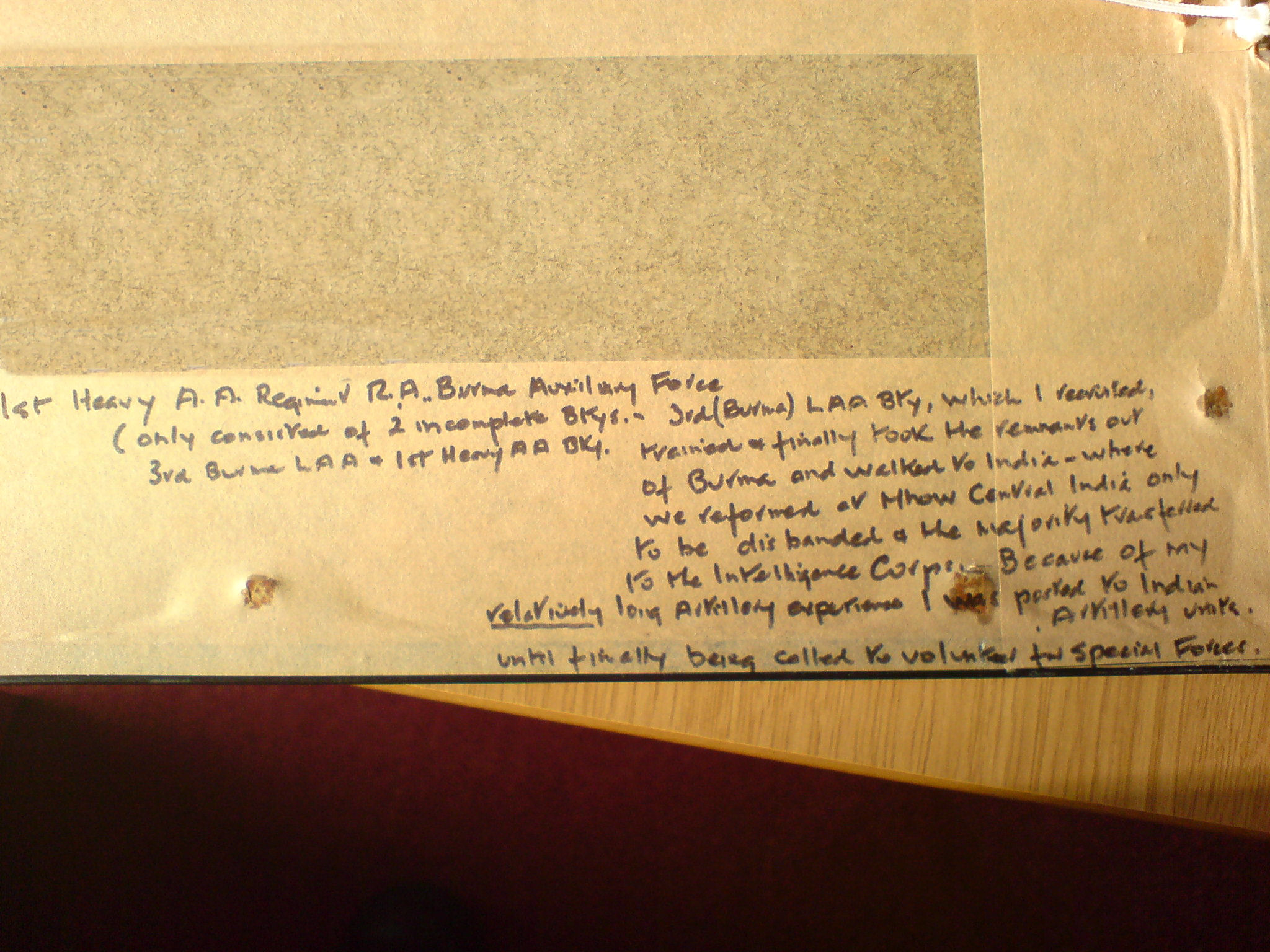

5. Captain Cockle's hand written notes on the reverse of photograph 4.

"1st Heavy A.A. Regiment, R.A. Burma Auxiliary Force (only consisted of 2 incomplete batteries - 3rd Burma Light AA and 1st Heavy A.A. Battery). 3rd (Burma) LAA Battery, which I recruited, trained and finally took the remnants out of Burma and walked to India - where we reformed at Mhow Central India only to be disbanded & the majority transferred to the [Burma] Intelligence Corps. Because of my relatively long artillery experience I was posted to Indian artillery units, until finally being called to volunteer to Special Forces."

Click image to open full size in new window

6. Surviving officers and men of the 3rd LAA Battery, Burma Auxiliary Force on being reunited at Mhow, India shortly before being disbanded, May 1942.

Captain Cockle is seated 5th from left , 2nd row from the front.

Click image to open full size in new window

25 February 2020