Loss of the Shan States - Burma 1942

Background

British pre-war planning considered that if the Japanese were to attack Burma they would do so through Thailand. It was though the Japanese would choose one of two main options. The first was and attack across the Dawna Hills into Tenasserim, followed by a drive northwards aimed at Rangoon. The second and perhaps main option, it was thought, was a thrust north eastwards into the Southern Shan States from the Chiengrai-Chiangmai area. There were relatively good land communications inside Thailand towards the Burma frontier. Although the routes across the frontier itself were limited to tracks, once inside Burma the Japanese would head straight for the roads on the Tachilek - Keng-Tung –Thazi and the Mongpan-Thazi routes.

The possibility of a Japanese invasion of Burma also brought about a change of strategy with regards co-operation with the Chinese. The Chinese offered to send two armies to help defend Burma, the Fifth and Sixth, each about the equivalent on size of a British division but with far less equipment. The Britis accepted but at first wanted these troops to remain inside China but close to the border with Burma where they would provide a reserve until Japanese intentions were revealed. Liaison was established with the Chinese and it was agreed that one regiment of Chinese troops would move up to the Burma border early in December 1941. This unit was to be available to move into Burma to support the British in the event of a Japanese attack into the Southern Shan States.

British Dispositions in The Shan States

Within a week of the Japanese commencement of war against the United States, Britian and other colonial powers, during December 1941 the British decided that the paucity of troops and modern equipment meant that the only plausible strategy was to defend the frontier for as long as possible. The 1st Burma Infantry Division had been formed in July 1941 with three brigades under command. Of the three, Burma Command now sent two into the Southern Shan States; the 1st Burma Infantry and the 13th Indian Infantry Brigades. Two Burma Frontier Force detachments, F.F.3 and F.F.4, were also in this area. F.F.5, consisting of only one column of around 100 men was left to cover Kerenni. The 2nd Burma Infantry Brigade, with F.F.2 under command, was disposed to defend Tenasserim. The Headquarters of the 1st Burma Infantry Division remained in Toungoo, far distant from any of its brigades. Elsewhere, a force of roughly a brigade in strength was left in Rangoon and in Central Burma there were a several units of the Burma Frontier Force and The Burma Rifles.

Irregular Forces

A number of irregular units came to be present in the Shan States in early 1942. Some were able to hinder the Japanese advance, primarily by carrying out demolitions of roads and bridges.

During 1941, a Bush Warfare School had been established at Maymyo (today Pyin Oo Lwin) to train Australian, British and other troops in guerilla warfare for the British Military Mission to China. Once trained, the men were to be sent to China where they would be attached to Chinese military units to provide advice and training. It was a highly covert operation aiming to support the Chinese against the Japanese invader at a time when open hostilities between the empires of Britain and Japan were to be avoided at all costs. It went under the name of Mission 204 and was also known as 'Tulip Force'. In October 1941, Major Michael Calvert, later of Chindits fame, was appointed commander of the School. When the war with Japan began in December 1941, many of the trainees at the Bush Warfare School were formed into three Special Service Detachments (S.S.D.s), numbered 1-3, and referred to as 'Commandos'. For a brief period, from March 1942, Colonel Order Wingate was placed in command of the S.S.D.s with the intention or mounting long range penetration operations against the Japanese. However, it proved impossible to mount such operations and with the situation in Burma on the verge of collapse, Wingate left for India in April. Of the S.S.D.s, numbers 1 and 2 were present in the Shan States during the Japanese invasion, though neither appears to have been in action against the invader. No.1 S.S.D., under Lt. Colonel J. Milman, found itself abandoned by the British and the Chinese and marched into China from where the unit was later flown to India. Lt. Colonel H.C. Brocklehurst led No.2 S.S.D. which found itself in Taunggyi as the Japanese approached during April 1942. The only other British troops in the area were Burma Frontier Force men of the Southern Shan States Battalion and a Burma Territorial Force unit of the Burma Rifles, the 14th Battalion. These elements were ordered to form a rear party under Brocklehurst, to cover the evacuation of Taunggyi until the Chinese withdrawal reached a line just south of the Taunggyi-Hopong road. On the evening of 20th April, Brocklehurst ordered the immediate evacuation of Taunggyi as Chinese resistance to the south had collapsed. During the withdrawal and trek to India, Brocklehurst's party split into smaller and smaller groups to evade the Japanese. Brocklehurst was drowned fording a river on 1st June.[1]

Before the start of the war with Japan, the Government of Burma had sanctioned the raising of Karen, Lahu and Kachin Levies. However little was done until the Japanese invaded. In February 1942, with the help of the Oriental Mission (established by Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.) in Singapore in May 1941), Lt. Colonel H.N.C. Stevenson, began to organise levies from amongst the Karen tribesmen in the Shan States. Before the war, Stevenson had served with the Burma Frontier Service and had extensive experience of working with the Karens. He was commissioned into the Army in Burma Reserve of Officers on 24th January 1941. Stevenson recruited a number of British civilians, all of whom were hastily commissioned into the Army, and began to organise the Levies. There was little time, few resources and next to no equipment, but many Karens were organised to keep watch on Japanese movements and to identify Burmese collaborators. As we shall see later, a group of Karen Levies, assisted by a company of regulars, fought hard to delay the Japanese advance from Toungoo to Mawchi. Stevenson and his officers, at times supported by officers of the Oriental Mission, were active in demolitions of roads and bridges.[2]

Entry of the Chinese into the Shan States

Japanese Conquest of Central Burma

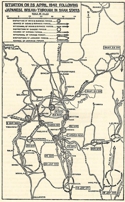

Source: “U.S. Army In World War II: China-Burman-India Theater: Stilwell's Mission to China”; found on the Hyperwar website, access January 2018

Click image to open full size in new window

Early in January 1942, the Chinese 227th Regiment of the Chinese 93rd Division had taken over the defence of the Mekong River east of the Kengtung-Mongpyak road. This greatly eased the burden carried by the 1st Burma Infantry Division. However, the Shan States and Karenni, with their long border with Thailand, still represented a huge area to be defended by just two brigades of the 1st Burma Infantry Division and a few small units of the Burma Frontier Force. Although the Japanese were inactive in this region during January and February, the large numbers of their troops and the Thai Army in northern Thailand were difficult to ignore. Yet despite this, the British steadily withdrew troops from the Shan States to reinforce the defence of Tenasserim. During this period, the 1st Burma Infantry Division gave up the; 2nd Battalion, The King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry; the 5th Field Brigade, Burma Auxiliary Force; the Malerkotla Sappers and Miners; and, later, the 1st Battalion, The Burma Rifles. On 19th January, the remainder of the Chinese 93rd Division was sent to Kengtung and later that month the entry of the 49th Division was agreed. This was followed by the arrival of the Chinese 55th Division in early February and these three divisions made up the Chinese Sixth Army. As the Chinese began to arrive, the remaining units of the 1st Burma Infantry Division left the Shan States and moved down through the country to defend the Sittang Valley south of Toungoo.

At the end of January 1942, it was decided to allow Chinese troops to enter the Shan States, where they would be available to free up British forces to concentrate in southern Burma with the aim of holding up the Japanese advance in the area where they had the best communications and which presented the greatest threat to Rangoon and communications with China. The Chinese Fifth Army began moving to the Toungoo area on around 29th February but only the 200th Division would arrive in Burma before the fall of Rangoon. By then it had been decided that the British would concentrate in the Irrawaddy Valley and for the Chinese to be responsible for the defence of the Sittang Valley. With the Chinese Sixth Army already in position in Karenni and the Shan States, an additional Chinese Army, the Fifth now began to arrive to defend the Sittang Valley south of Mandalay to Toungoo. From the middle of March, the 1st Burma Division began to withdraw northwards towards Toungoo in preparation for transfer to the Irrawaddy front, whilst the Chinese Fifth Army moved in to take over.

Chinese formations were small when compared with the equivalent formations of other armies. A Chinese army was roughly equivalent to a division in strength; a division roughly equivalent to a regiment or brigade; a regiment equivalent to a battalion.

The Battle for Toungoo and the Japanese Drive on Mawchi

The Chinese were not prepared to defend further south than Toungoo however by 11th March, the Chinese 200th Division was dug in Toungoo at with the divisional cavalry holding the river line to the south, centred on the town of Pyu, astride the road and railway line running north to Toungoo. The Japanese first contacted the Chinese at Pyu on 18th March where they were held up in heavy fighting for three days before forcing the Chinese back to Oktwin. Having eventually pushed passed and around Oktwin, on 24th March the Japanese made their first attack on Toungoo. They succeeded in encircling Toungoo from the west and the north. In the north, at Toungoo airfield, they engaged the tail of the British 1st Burma Division which was completing its transfer to the Irrawaddy front by rail. There now followed a fierce battle to oust the Chinese from Toungoo.

The Chinese defenders of Toungoo, the 200th Division, eventually gave way to superior Japanese forces and the survivors fought their way out of the city to the north on 29th March 1942. The Chinese then established a line of defence in the Sittang Valley south of Yedashe. Before their withdrawal, the defenders of Toungoo did not destroy the important bridge across the Sittang River to the east of the city and this left open the road to Mawchi and Bawlake. The bridge had been prepared for demolition by the British prior to handing it over to the Chinese.

There was a Chinese detachment at Mawchi but between these troops and Toungoo there was only a party of Karen Levies, reinforced by a Karen company detached from the 1st Battalion, The Burma Rifles. The Japanese immediately set off along the Mawchi road, their eventual goal being Lashio far to the north. General Liang, vice-commander of the 55th Chinese Division, and commander of all Chinese troops in Karenni, refused to move further west than Mawchi. The General believed that Mawchi was the western boundary of his area of responsibility, outside of which he could not venture without instructions from higher authority. He also made the valid point that the troops under his command were too few to hold both Mawchi and the Salween front. Part of his division, the 1st Regiment, was in Karenni, defending the road between Mawchi, Bawlake and Loikaw. A battalion of the 2nd Regiment was also in Loikaw while the 3rd Regiment was in Thazi, to the north of Toungoo and unable to intervene on the Mawchi road.

The Japanese sent troops of the 56th Division eastwards along the road to Mawchi. The divisional records recount that they were first engaged at Alemyaung and then at Mawchi, which they occupied on 4th April. The Karen Levies and the Karens of the 1st Burma Rifles were unable to delay the Japanese for long but did carry out demolitions along the road. However they were unable to cover these with any defence and thus the delays inflicted on the Japanese were less than they might otherwise have been. The Chinese 1st Regiment then concentrated in the Bawlake-Kemapyu area, astride the road that ran up the valley of the Nam Pawn River.

Heavy fighting between the Chinese and Japanese now followed in the area to the south of Namphe and Bawlake. At the same time, the Chinese attempted to concentrate troops to the north, around Loikaw. On the night of 18th/19th April the Chinese 55th Division covering the Mawchi-Loikaw-Taunggyi road was destroyed south of Loikaw. On 19th April, Japanese tanks were met only nine miles south of Loikaw. The Chinese Sixth Army Headquarters left for the To Sai Hka Bridge across the Nam Tamphak River. Only a few guards and a company of Chinese engineers remained in Loikaw to cover the two bridges over the Balu Chaung and to carry out demolitions.

The Karen Levies were in contact with the Japanese at Yado. There was every possibility that the Japanese would attempt to move along the Mongpai [Mong Pawn?]-Pekon [nr Loikaw?] road and outflank the Chinese, reaching the Loilem-Kengtung road behind them. The Levies[?] sent a strong patrol to Mongpai to prevent this but they were too late and it was found that the Japanese already held the road.

The Japanese Drive on Lashio - Loss of the Shan States

Near the end of March 1942, General Alexander had a plan drawn up for the defence of Upper Burma and a fighting withdrawal to India and China in the event that Mandalay could not be held. A key concern was to provide support to the Chinese Armies as part of the Allied high level strategy of keeping China in the war. Under Alexander's plan only a portion of the British and Indian forces, the 1st Burma Division, less one brigade, would fall back along the route to India. The 17th Indian Division, less one brigade but reinforced with a brigade of the 1st Burma Division, was to withdraw astride the Mandalay-Shwebo-Katha road, thus protecting the projected supply route to China via the Hukawng Valley. Later it was to move to Kalewa or Bhamo. Maintaining contact with and providing support for the Chinese Fifth Army was to be the responsibility of the British 7th Armoured Brigade and a brigade of the 17th Indian Division. These were to accompany the Chinese as far as Lashio and then, if required, withdraw towards Bhamo. The Chinese Fifth Army was to defend the area along the Mandalay-Lashio road, the main Burma-China route. The Chinese troops of the Sixth Army in the Shan States were to withdraw on two axes. Those elements, mainly the 93rd Division, to the east of the Salween River were to withdraw via Kengtung towards Puerh in China. The remainder, mainly the 49th and 55th Divisions were to fall back from Loikaw and Mongpan to Loilem and from there via Hsipaw to Lashio and China .

However by April, it was realised that Alexander's plan could not be implemented. Given the loss of rice producing areas in Burma, the breakdown of the railways and the famine in Yunnan, it would be impossible to collect enough provisions in the Lashio area to feed the retreating Chinese Armies. The plan was now amended and agreed with the Chinese for the Fifth and most of the Sixth Armies to withdraw north via Shwebo and that no British forces should withdraw towards Lashio. In the end, these plans were overtaken by events in the Shan States where the rapid Japanese advance threatened the total destruction of the Chinese Sixth Army.

Despite the Japanese pressure on Loikaw, it had proved impossible to concentrate the widely dispersed Chinese Sixth Army behind the 55th Division and only a small force was available to oppose the Japanese motorised column now driving north (on Lashio?).

The Japanese came to the Sai Hka and on the afternoon crossed the bridge which the Chinese had failed to blow up. The Chinese fell back on Hopong and set up a strong position to the east, astride the road to Htamsang. On the morning of 22nd April the Japanese subjected the Chinese defenders to an almost continual aerial bombardment. Loilem too was bombed and a large part of the town burnt down. That night the Chinese pulled back to a position at Kang Nio, about eight miles west of Loilem. However the Japanese outflanked the strong natural defences here and the Chinese were unable to stop the Japanese entering Loilem on the evening of 23rd April. The Chinese, under General Kan, about 300 men, fell back and set up a new line on the Lashio road near Panglong.

During the fighting around Loilem, the Chinese 93rd Division had been moving from Kengtung to the assistance of their comrades. However, when only some twenty miles east of Loilem, they heard the town had fallen and then returned east to Takaw. Here they were joined by General Kan who had marched through the hills with a personal bodyguard. From Takaw, what remained of the Chinese 49th and 93rd Divisions headed to Kengtung where they were joined by General Chen and the survivors of the 55th Division who had made their way across country form the Bawlake area. The Sixth Army then marched off to China, leaving Kengtung to be occupied by the Thais.

With the Japanese across the Saik Hka by the afternoon of 20th April and the Chinese in the area pulling back towards Hopong to establish a line to the east of that town, Taunggyi and the road through it to Thazi and Meiktila were left undefended. The Chinese 200th Division was sent east from Meiktila on 21st April and two days later, supported by a regiment of the Chinese 22nd Division and under the direct command of General Stilwell, the Division attacked the Japanese holding Taunggyi. The town was captured by the Chinese the next day, 24th April, but despite advancing towards Hopong and reoccupying Loilem, they could not stop the Japanese drive on Lashio. There were few organised defenders to prevent the Japanese taking all of the Shan States and then northern Burma via Bhamo and Myitkyina.

Elsewhere there was a fear the Japanese in the Shan States might now be able to attack the rear echelons of the Burma Army from the east. A detachment was sent from the British Infantry Depot at Maymyo to hold the Gotkeik Gorge, thus offering some protection to the rear of the Burma Army. Alexander's Burma Army Rear Headquarters was relocated from Maymyo to Shwebo on 23rd April.

“On 18th April, the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo, commanded by Major Calvert, was ordered by Army Headquarters to send detachments to the Gotkeik area to prevent the Japanese from infiltrating along the main Lashio road. One party went to Nawngpeng and another to Nawngkio. These parties each formed a roadblock and sent out reconnaissance patrols. The next day a platoon from the British Infantry Depot arrived from Maymyo to support Captain Dunlop at Nawngpeng. This was followed next day by a half platoon ordered to support Captain Samuels at Nawngkio. The next day, 21st April, Major Calvert was ordered to form a battalion of four rifle companies from the convalescent personnel of the British Infantry Depot at Maymyo. During the day, 'A' Company moved to Wetwyn for to cover Maymyo. The Bush Warfare School detachments were ordered back from Gotkeik, the threat from that direction being thought to have gone away. The next day, Captain Dunlop blew the bridge over the Namtu River at Namlan. Captain Galbraith of the 8th Battalion, The Burma Rifles, led 'B' Company to Tawngpeng[?Nawngpeng?]. Captain Moore took 'B' Company to Tawngkio [?Nawkgkio?] and set up defences. On 22nd April the Depot left Maymyo for Sagaing and the Battalion was given an independent role to protect the Lashio Road. The next day orders were received to proceed to Sagaing and the following morning troops were pulled back in lorries to Maymyo from Gotkeik ...... The Bush Warfare School Battalion left Maymyo for Sagaing on 25th April where it came assumed an independent role under the direct command of Army Headquarters.” [3]

In addition, it appeared that the Chinese defences around Pyawbwe, south of Mandalay, were in grave danger. With the loss of the Shan States imminent and given the threat to Mandalay from the south, on 25th April General Alexander ordered the withdrawal of British and Chinese troops to the north of Mandalay.

The Headquarters of the Chinese Sixty-Sixth Army and parts of the 29th and 28th Divisions now arrived in Lashio and the Army Commander, General Chang, assumed command of all Chinese troops in the area. On 27th April, the 28th Division was sent south from Hsipaw to Namon on the Loilem road. During the night it contacted a Japanese motorised column which was forced to retreat. Fearing he would be outflanked, the Chinese commander also retired and went to Lashio. Throughout this time, motor transport and armoured vehicles of the Chinese Fifth Army were flooding through Lashio to China but none of it was directed against the Japanese. The Japanese drew up to Lashio and on 29th April, amidst heavy fighting, the Chinese destroyed their stores before retreating to Hsenwi and taking up positions across the road to Kutkai. The Japanese entered Lashio the same day. The Chinese then withdrew into China through Kutkai and Wanting. In the meantime, the Japanese pressed on to Bhamo.

The final act of the Chinese defeat in the Shan States was the escape of the 200th Division, with its attached regiment of the 22nd Division. This force had earlier retaken Loilem from where it moved to Hsipaw with the intention of reaching Lashio. Finding that Lashio had fallen and was too strongly occupied to be attacked, the Division headed south west and briefly entered Maymyo. From here it went north to Mogok with the objective of fighting its way out to China. At Mogok was a detached regiment of the 28th Division.

The Fall of Bhamo and Myitkyina

Between the Japanese and Bhamo lay the Shweli River which was bridged at Manwing. The bridge was defended by the Northern Shan States Battalion, Burma Frontier Force [and elements of a detachment of the Chin Hills Battalion] which had withdrawn from Lashio when the Chinese left. The bridge was prepared for demolition but no officer experienced in demolition work remained at the bridge. On 3rd May, a column of Japanese lorries armed with machine guns approached the bridge and rushed the defending troops. The fuses of the demolition charges were damp and did not ignite and the Japanese captured the bridge intact. There were no other demolitions carried out along the Lashio-Bhamo road and the Japanese drove in to Bhamo the next day.[4]

The Japanese then set off for Myitkyina. Other than disorganised units of the Burma Frontier Force and the trainees and stragglers of the 9th (Reserve) Battalion, The Burma Rifles, there were no troops to defend the Bhamo-Myitkyina road. No demolitions were carried out. The Japanese overtook some units retreating along the road from Bhamo to Myitkyina and dispersed them or made them prisoner. Against almost no resistance and delayed only by groups of demoralised soldiers and civilian refugees, the Japanese drove on to Myitkyina. The town was evacuated by the British on 7th May and the Japanese entered the next day.[5]

Escape to China and India

Many soldiers and civilians headed for India via the Hukawng Valley, to the east and north of Myitkyina. Others travelled up the road to Sumprabum and on to Fort Hertz. The Sumprabum road saw effective demolition work by officers of the Oriental Mission/Kachin Levies which caused great delay to the Japanese who had to repair every steel suspension bridge they came to.[6]

03 January 2018

[1] "The Bush Warfare School Commandos", The Soldier's Burden web site (www.kaiserscross.com) accessed January 2018; War Diary 14th Burma Rifles, WO 172/986 (War diary 14th Burma Rifles).

[2] IOR/L/WS/1/1313; "Burma Levies - Karen Levies 1942", WO 203/5712; "SOE Oriental Mission” Raising the Burma Levies during WW 2 [1941 to 1942]", Vivian Rodrigues (unpublished 2017); H.N.C. Stevenson, IOR/L/I/1/1525; Burma Army List 1943.

[3] “Bush Warfare School”, WO 172/1453

[4] WO 203/5712

[5] “Personal Diary of events in Burma prior to and during the campaign with an account of the retreat through the Hukong [sic] Valley”, Edward Hewitt Cooke, National Army Museum Acquisition No.1972-02-44

[6] “The Hump, The greatest untold story of the war”, Bernard J, Souvenir Press (1960)