Trooper John William Marrison, 150th Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps

Trooper John William Marrison, known to many as “Jack”, served as a tank driver with the 150th Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps (York and Lancaster) in the United Kingdom, India and Burma. He fought in and survived several encounters with the Japanese before he was wounded near the Irrawaddy River in Burma on 3rd February 1945.

Trooper Marrison came from Sheffield where he worked in the steel industry for which the city was once famous. When he first tried to join the Army he was turned away as his job was one of those protected as being vital to the war effort. He then went to neighbouring Rotherham where he told the recruiting authorities that he was a labourer and he was signed up into the Army.[1]

The 150th Regiment, R.A.C. began life as the 10th Battalion, The York and Lancaster Regiment, which began forming at Pontefract on 23rd June 1940. The new battalion moved to Paisley in Scotland where in October it became part of the 207th Infantry Brigade Group. Trooper Marrison joined the Battalion at Paisley on 26th July 1940, as one of an intake of 850 civilian recruits, most of whom came from Sheffield. Following months of training, in November 1940, the 207th Infantry Brigade moved to Essex and the 10th Battalion became attached to another brigade, occupying a sector of the coastal beach defences near Clacton.

Sheffield was heavily bombed on two nights in December 1940. Trooper Marrison was given compassionate leave to visit his wife and two young children. Mrs Marrison and her children had been sheltering in a cellar when bombs dropped only a few hundred yards away. They had to be dug out after nine hours in the cellar. In two nights of bombing, nearly 700 civilians were killed. When his two days’ leave was up, Trooper Marrison had to return to his unit and went to Sheffield station to catch the train. On the platform, while saying goodbye to his wife, two Red Caps (Royal Military Policemen) approached him, shouting at him to board the train which was ready to leave. Trooper Marrison responded and left the Red Caps in no doubt what would happen to them should they disturb him again. He completed his goodbyes, boarded the train and did not return home to Sheffield until five years later.[2]

Sheffield in flames – taken in the aftermath of one of the raids of December 1940.

(U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

In February 1941, the Battalion rejoined the 207th Infantry Brigade near Epping, and after two months’ training returned to the coast, this time near Southend. On the night of 10th/11th May 1941, the Battalion suffered its first casualties when a junior officer and nine men were killed in a German air raid.[3]

In July, the infantry battalions of the Brigade heard for the first time that they were to convert to a new role, as tank regiments of the Royal Armoured Corps. The 10th Battalion and the two other battalions of the Brigade moved to Cheltenham in August where the 10th Battalion became the 150th Regiment, R.A.C. As the establishment of a tank battalion was much smaller than that of an infantry battalion, some 300 officers and men were posted away. On 26th August 1941, the Regiment, together with the 146th and 149th Regiments, R.A.C., embarked at Liverpool for India, sailing with convoy WS 11. After a voyage lasting more than three months, the men disembarked at Bombay in early December. The 150th Regiment went to Dhond (Daund), near Poona (Pune) where it formed part of the new 50th Indian Tank Brigade. It was expected that this formation would be trained in mobile, desert warfare for service in the Middle East or North Africa. However, there was little equipment and few vehicles, only a handful of Valentine tanks, so it seemed that it would be a long time before the Regiment went to war. It was also a time of anxiety for the men, given that Sheffield had once again been bombed.[4]

The outbreak of the war with Japan put to rest all ideas of service in the desert. The 50th Indian Tank Brigade moved to Ranchi in July 1942 but the 150th Regiment went instead to join the 19th Indian Infantry Division in the Madras area where it stayed for nine months. After this, the Regiment returned to the Poona area, this time to Ahmednagar. During the winter of 1943-1944, the Valentine tanks which had equipped the Regiment began to be replaced by American M3 ‘Lee’ tanks, but the new tanks arrived only slowly. The arrival of the Lee forced a reorganisation given the difference in tank crew size between the Valentine and the Lee; the latter having a crew of seven men. During this time, the Regiment carried out intensive training with the British 2nd Infantry Division.[5]

Members of the 150th Regiment, R.A.C. Trooper Marrison is standing with arms folded, middle row, 4th from the left.

(Marrison family)

In the spring of 1944, the Japanese launched their major offensive on North East India. Their aim was to capture the great base at Imphal. Japanese pincers closed in on the area from the south and the north. Other Japanese troops headed for Kohima, intending to cut the road between Imphal and the Manipur Road railhead at Dimapur, preventing any reinforcements arriving from India. After initial gains, the Japanese were held by IV Corps at Imphal but Dimapur was threatened by the Japanese thrust on Kohima, which came under direct attack for the first time on 5th April 1944.[6]

When the Japanese offensive began in March 1944, the 150th Regiment was still at Ahmednagar and was still in the midst of reorganisation. Only ‘C’ Squadron had been completely equipped with Lee tanks and was undergoing jungle training 170 miles away near Belgaum. The Squadron was now called upon for urgent despatch to Dimapur to reinforce the British and Indian troops fighting to defeat the Japanese offensive. Having been recalled to Ahmednagar, ‘C’ Squadron set off for Dimapur in two groups. One party, led by Captain W.A. Boyce, flew from Poona aerodrome to Dimapur on 31st March, where they spent the next nine days preparing sixteen Lee tanks collected from reserve storage before moving off to support the 49th Indian Infantry Brigade on the Imphal-Tiddim Road near Bishenpur. Captain Boyce’s squadron operated with the 3rd Carabiniers as a temporary fourth squadron, being referred to as ‘YL’ Squadron to differentiate it from ‘C’ Squadron of the 3rd Carabiniers.[7]

Meanwhile, a second party commanded by Major A.H.F. Newman, with men from ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ Squadrons, sixteen Lees and other vehicles, had left Ahmednagar by rail on 30th March 1944 and was also headed for Dimapur. Trooper Marrison was one of this party. The rail party arrived at Dimapur on 11th April and formed a detachment of five tanks as there were insufficient trained men to provide crews for all the tanks. The detachment was so short of men that it had been necessary to augment these five crews with men from other units at Dimapur: R.E.M.E. artificers; gunners and signallers from the 2nd Infantry Division. The detachment commander was Lieutenant R.H.K. Wait, who led from tank 26138. Trooper Marrison was the driver of this tank.[8]

Three days before the rail party of ‘C’ Squadron, 150th Regiment arrived at Dimapur, the Japanese had encircled Kohima. They had also got around behind the 161st Indian Infantry Brigade on the Dimapur-Kohima Road and established a roadblock at around Milestone 38 near Zubza, cutting off the 161st Indian Infantry Brigade in the area between Jotsoma and Kohima from the British 2nd Infantry Division, now moving down the road from Dimapur. By the evening of 9th April, the British 5th Infantry Brigade was ready to advance towards Zubza and by midday on 11th April, the 7th Battalion, The Worcestershire Regiment was in action against the roadblock. The Japanese were dug in on a steep ridge astride the road near Milestone 38 and a frontal attack was found to be impossible. As the British infantry manoeuvred to attack the ridge, Lt. Wait’s detachment of five Lee tanks was brought forward by tank transporter on the afternoon of 13th April. The task of this detachment would be to provide close support for the infantry as they attacked the Japanese bunkers on the ridge. The journey to Zubza was slow; it was realised that the tanks would have to be unloaded from the transporters in order to cross each bridge encountered. There was also considerable traffic congestion. It was therefore decided that the tanks should complete the journey on their own tracks and they left the transporters at the first bridge. The tanks finally arrived at their harbour for the night, near Zubza, at around 0030 on 14th April. Close protection for the tanks was provided by a platoon from the 2nd Battalion, The Norfolk Regiment.[9]

A Lee tank being carried by a tank transporter. This photo was taken at the southern end of the Imphal plain.

(H.M.S.O.)

In the early hours of 14th April, the Japanese approached the harbour but were driven off by the infantry protecting the tanks. A large detachment of Japanese was spotted moving through the trees. The Norfolks’ platoon commander, Sergeant Fred Hazell, warned his men to get ready, although he was frustrated to find that the tank crews were slow to react as “they were all wrapped up in their bedding fast asleep under the tanks”. The men of the Norfolks’ platoon opened fire, forcing the Japanese to take cover and return fire. The exchange of fire lasted nearly an hour during which three men of the 2nd Battalion, The Norfolk Regiment were wounded. It was later reckoned that the Japanese had suffered thirty four killed.[10]

Further attacks came in and were engaged by tank fire and the small arms fire of the crews of the accompanying soft vehicles. Once again, considerable casualties were inflicted upon the Japanese. When a further attack failed, the Japanese withdrew under heavy mortar fire and at 0815, the infantry of the 7th Battalion, The Worcestershire Regiment asked the tanks to cease fire as they were about to attack the Japanese positions. Fifteen minutes later, the infantry attacked and captured the Japanese positions. The tanks remained in the harbour and stood down at 0930. The only casualty was Lieutenant R.H.K. Wait who received a slight wound to his neck.[11]

Later that same day, the tanks supported a company attack by the 1st Battalion, Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders against Japanese bunker positions 300 yards east of the road at Milestone 38. Following a very heavy artillery barrage, the tanks conducted direct fire against the known bunkers and continued to give supporting fire as the infantry went in. The bunkers were taken against negligible opposition and with few casualties. The Japanese counter-attacked but were driven off with heavy losses. Contact with the 161st Indian Infantry Brigade around Jotsoma was made and the road between Dimapur and Jotsoma was now re-opened. The tanks returned to the previous harbour for the night. Shortly after dawn on 18th April, infantry of the 16st Indian Infantry Brigade, supported by three Lees of ‘C’ Squadron under Major Newman, moved down the road towards Kohima and the siege was lifted. There was much hard fighting to come before the Japanese were finally driven away.[12]

During the fighting of 14th April, Trooper Marrison was the driver of the detachment commander’s tank, Lieutenant Wait. The crew of this tank, serial number 26138, was:

- commander: Lieutenant R.H.K. Wait

- driver: Trooper J.W. Marrison

- operator: Corporal L. Nicholas

- 75mm gunner: Trooper C. Hopkins

- 75mm loader: Sergeant J. Willis

- 37mm gunner: Trooper M.W. Morton

- 37mm loader: Signalman W. Dyer.

On 17th April, Lt. Wait swapped tanks to lead three Lees to support the infantry near Jotsoma. Two Lees remained at Zubza, including Trooper Marrison’s tank which was now commanded by Sergeant J. Blackburn. Other than Sergeant Blackburn, the crew of tank 26138 remained unchanged.[13]

The M3 Lee needed a seven man crew, all of whom can be seen in this photo of a tank belonging to the 3rd Carabiniers, taken near the Mu River, January 1945.

(Imperial War Museum)

Lt. Wait’s detachment was not in serious action again and about the middle of May it was withdrawn to Dimapur. The two separate detachments of ‘C’ Squadron were united later that month but held in reserve. At the end of July, with the Japanese now in full retreat, the Squadron returned to Ahmednagar.[14]

By the end of September 1944, the 150th Regiment had been completely equipped with Lee tanks and was then ordered to Burma. It arrived at Imphal at around 15th October 1944 and joined the 254th Indian Tank Brigade. This brigade was allotted to XXXIII Indian Corps for the advance into Burma but did not at first join the Corps in its drive to the Irrawaddy River. The 150th Regiment moved by stages from Imphal, beginning shortly after Christmas Day 1944. It caught up with the 19th Indian Infantry Division towards the end of January 1945.[15]

On New Year’s Eve 1944, while “out in the jungle”, a truck pulled up near to where Trooper Marrison and his mates were resting. The truck was carrying a cask of rum and the driver, upon being asked by Trooper Marrison, said no, it wasn’t for them but the officers. Trooper Marrison drew his pistol, one that all tank drivers carried, and called out to the driver that there would be trouble if he and his mates did not received some of the rum. Marrison was immediately detained under guard but the next morning he was released and he and all his mates received a ration of rum. No further action was taken.[16]

("Official History of the Indian Armed Forces in the Second World War, 1939-45; Reconquest of Burma, Volume II", Prasad N., Orient Longmans (1959))

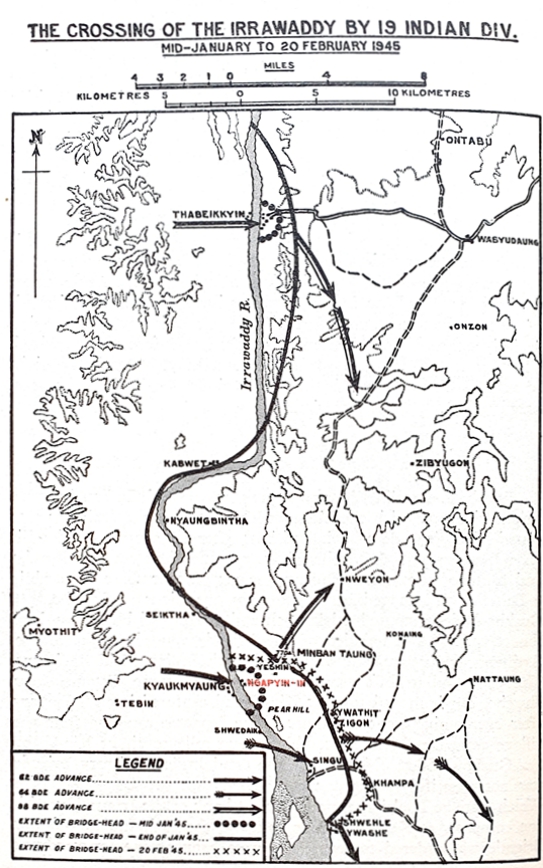

The 19th Indian Infantry Division, supported by the tanks, had advanced from the Indian border to the Irrawaddy River, arriving at the river to the north of Mandalay in early January 1945. On the night of 14th/15th January, a crossing of the Irrawaddy River was made near Kyaukmyaung, taking the Japanese by surprise. Having been caught off balance, the Japanese quickly recovered and attempted to eliminate the initial lodgement. Heavy fighting took place on the east bank of the river well into February.[17]

Given that the initial bridgehead established opposite Kyaukmyaung covered only a small area, it was decided that only half of ‘C’ Squadron, 150th Regiment, R.A.C. would be put across the river into what was termed in one report, the ‘lodgement’. The beach on the river bank was under observed artillery and small arms fire. During 1st February, an advance party from ‘C’ Squadron with ‘A’ Company, 3rd Battalion, 4th Bombay Grenadiers, crossed the river into the position near Ngapyin-In, then being called ‘Needle Box’. This detachment was tasked with preparing slit trenches and bunkers for the tanks and their crews. That night, 1st/2nd February, eight tanks were rafted across the river from Kyaukmyaung into the lodgement under the cover of deception measures, which included the use of aircraft flying over the crossing point to mask the noise of the tanks. These measures were only partially successful and there was some shelling by the Japanese. One trooper of the Regiment was wounded and an engineer was killed.[18]

Trooper Marrison recalled that as his tank was ferried across the river, his tank commander told him that he wanted to earn the Military Medal. Marrison gave an expletive-laden reply to the effect, “Well don’t get me one, I want to get home in one piece!” [19]

A Lee tank being loaded onto a pontoon ferry by men of the 2nd Division before crossing the Irrawaddy River at Ngazun, 28 February 1945. The tanks of ‘C’ Squadron, 150th Regiment, R.A.C. would have used such a ferry to cross the river to Ngapyin-In on 1st February 1945.

(Imperial War Museum)

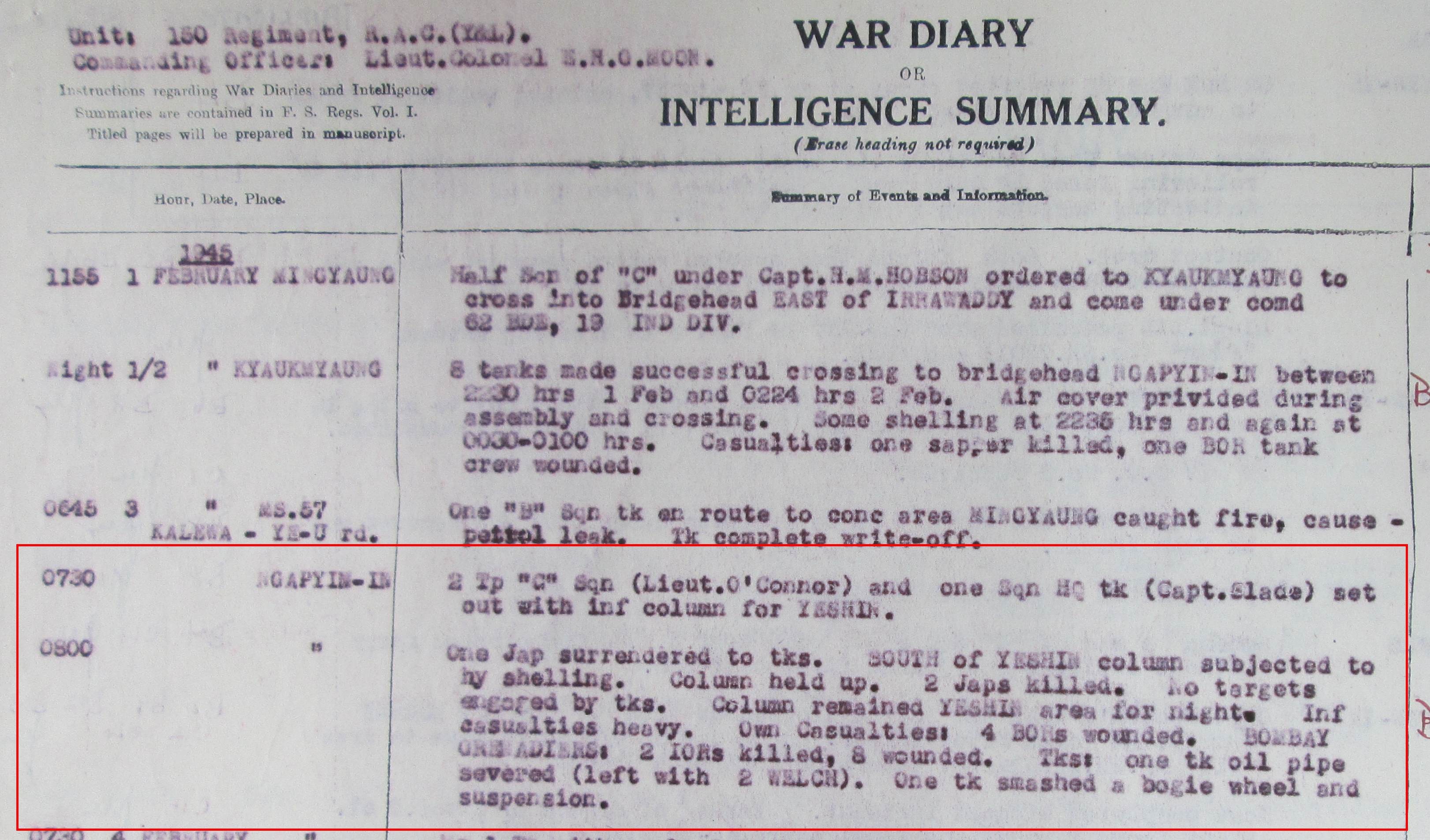

On 3rd February 1945, 2 Troop of ‘C’ Squadron under the command of Lieutenant O’Connor and with one tank from the Squadron Headquarters commanded by Captain Slade, set out in support of an infantry column. The infantry were the 4th Battalion, 6th Gurkha Rifles whose objective was to advance from the area of Ngapyin-In through Yeshin, a village to the north-east, to clear yet another village beyond, called Wettagon. Thick jungle prevented the tanks from identifying any targets but on the way, one Japanese soldier surrendered to the tanks and two others were killed by the infantry. Then the column was held up by Japanese shelling, in the area south of Yeshin. This proved to be one of the heaviest Japanese artillery concentrations of the campaign. It came down upon the tanks as they moved over open ground towards the village. The Japanese used the full range of guns available to them: 75mm, 105mm and 150mm. The Gurkhas suffered severe casualties, 22 killed and 87 wounded. The 2nd Battalion, The Welch Regiment in Ngapyin-In also suffered from the shell fire but was able to form additional stretcher bearer parties to help bring in the wounded. However, the 2nd Welch lost 19 men killed and 32 wounded. The troops relied upon pack mules to carry supplies and these too were caught by the artillery, some 120 of these dependable animals were killed. The Japanese artillery also caused casualties amongst the tanks of ‘C’ Squadron, two of which were damaged. One tank had an oil pipe severed and was left behind for repair. Another had a bogie wheel smashed with damage to the suspension.[20]

Extract from the war diary, 150th Regiment, R.A.C. - February 1945.

(The National Archives, WO 172/7345)

When talking about his wartime experiences, Trooper Marrison mentioned that he held the Gurkha soldiers in great esteem, believing them to be the bravest soldiers he had ever come across. One Gurkha soldier in particular stood out in his memory. Under heavy fire, one of the tanks had broken down or been damaged and this Gurkha soldier attempted to attach a tow chain between this tank and another. He was out in the open, totally unprotected, and was killed outright. This brave man’s death is very likely to have occurred during the action near Yeshin on 3rd February 1945 as it appears to have been the only time that Trooper Marrison was in action alongside Gurkha soldiers. There can have been no subsequent occasion as Trooper Marrison was evacuated due to wounds received on 3rd February.[21]

As was usual, the tanks were accompanied by Indian troops of the 3rd Battalion, 4th Bombay Grenadiers, whose job it was to protect the tanks from Japanese infantry. In addition to the casualties suffered by the infantry of the Gurkhas and the 2nd Welch, there were also losses amongst the Bombay Grenadiers – two men were killed and eight wounded.[22]

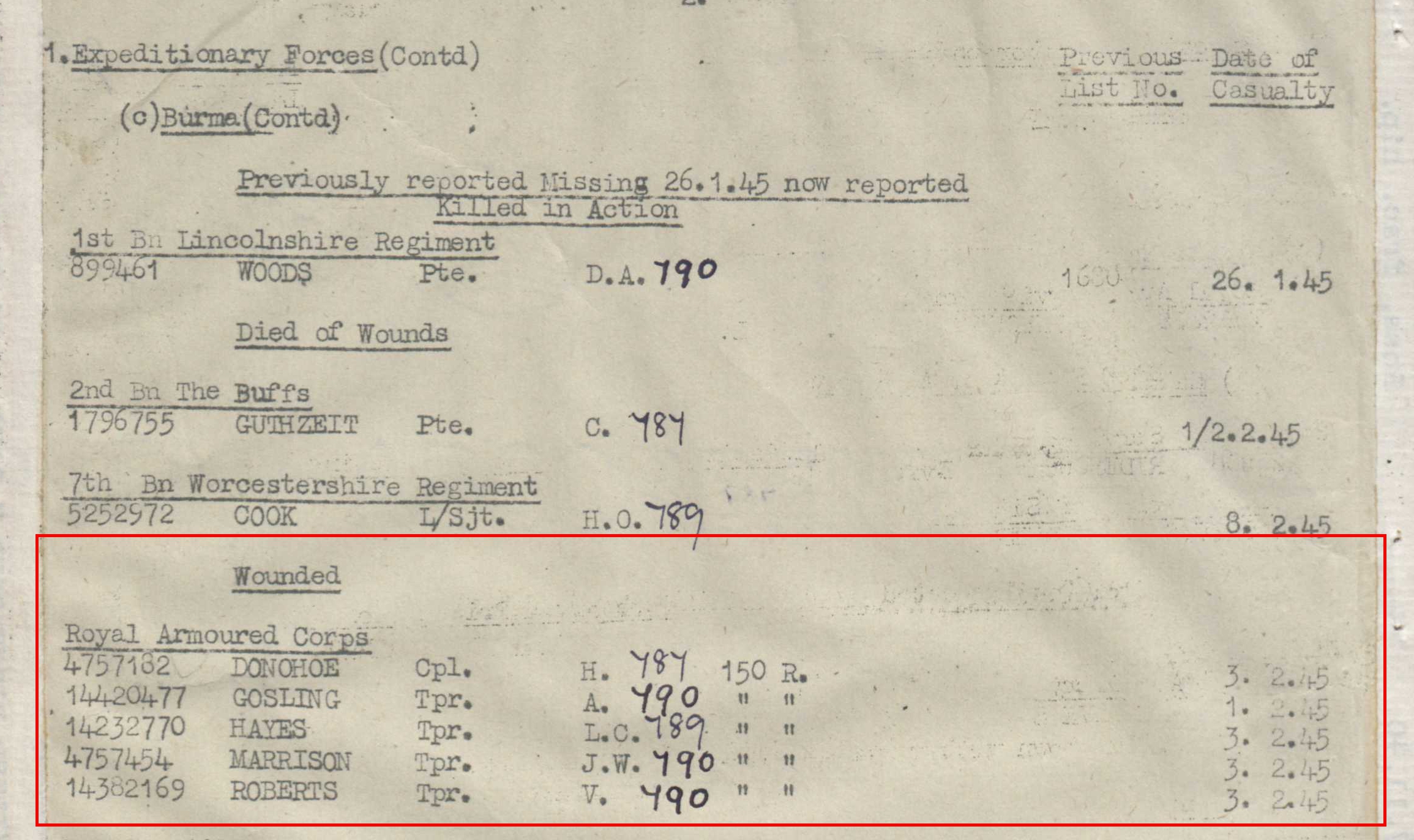

In ‘C’ Squadron, there were four casualties, all reported as wounded. In the official casualty report for that day, the men of the Regiment wounded were:

- Corporal H. Donohoe

- Trooper L.C. Hayes

- Trooper J.W. Marrison

- Trooper V. Roberts.

The casualties of the 150th Regiment, R.A.C., suffered in early February 1945.

(British Army Casualty Lists 1939-1945, FindMyPast)

Trooper Marrison was wounded when a Japanese shell hit a tree and splintered. His good friend, Corporal Harold Donohoe, also from Sheffield, was wounded at the same time. It seems that the men were refuelling their tank from jerry cans when they were caught by the Japanese shelling. It was one of war’s great coincidences, that Trooper Marrison was wounded in the same leg that his father had been wounded in on the Somme during World War One.[23] Sadly, it appears that Corporal Donohoe, a friend of Trooper Marrison, died of his wounds later that same day, as recorded in the official records and commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. He is now buried at Taukkyan War Cemetery, outside of Rangoon.[24]

Having been held up, the column remained in the Yeshin area for the night and the operation to clear Wettagon was abandoned the next day. An infantry company from the 3rd Battalion, 6th Rajputana Rifles and the remaining troop of tanks from ‘C’ Squadron were sent out to help extricate the Gurkhas. Japanese opposition was met on the way but successfully dealt with and the two forces were able to join up before setting out on the return march to ‘Needle Box’. The weakened 4th Battalion, 6th Gurkha Rifles carried their wounded out on improvised stretchers.[25]

The Kyaukmyaung ‘lodgement’ across the Irrawaddy River. Here, an amphibious DUKW vehicle crosses from the bridgehead near Ngapyin-In back to the west bank.

On 8th February, the half of ‘C’ Squadron, with ‘A’ Company, 3rd Battalion, 4th Bombay Grenadiers, a company of the 4th Battalion, 6th Gurkha Rifles and the 2nd Battalion, The Worcestershire Regiment conducted a successful attack to seize Kule, to the south of the lodgement. The attack began with a fifteen-minute aerial bombardment by ‘Hurribombers’, followed by a heavy artillery and mortar bombardment. Under the cover of this, ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies of the Worcestershire Regiment led the attack, each supported by a troop of tanks. After the tanks had shot up the edge of the village, ‘A’ Company was able to enter and after five hours of fighting the village was finally clear of Japanese. The tanks returned to harbour that night where they were joined by the remaining tanks of the squadron and the Tactical Headquarters of the Regiment which had crossed the river earlier. Although the security of the bridgehead was never in doubt, it was to take further hard fighting against a determined enemy before the 19th Division was able to break out of the bridgehead on 23rd February and head south for Mandalay.[26]

For Trooper Marrison, his wound meant that his war was over. He recalled being operated on by an Australian doctor “while still in the jungle.” He arrived home in Sheffield some six months later. Upon reaching Sheffield, he caught a tram home and the driver made him take pride of place at the front and he was given a round of applause. Shortly after getting home, John Marrison was taken into hospital with severe malaria. Having recovered, he returned to his old job as a drop stamper on the drop hammer in the foundry where he had worked before the war. Ironically, the hammer was of pre-war German manufacture and during the war it had produced crankshafts for Rolls Royce Merlin engines which powered Spitfires. After an industrial accident, John Marrison changed job to work in the melting furnaces where he stayed until he retired. He died in 1984, aged 71.[27]

I am indebted to the Marrison family for granting permission to publish the reminiscences of Trooper Marrison and the accompanying personal photographs.

19 December 2024

[1] Marrison family recollections, told to the author April 2020.

[2] Marrison family

[3] “The York and Lancaster Regiment, 1919-1953”, Sheffield O.F., Gale & Polden (1956)

[4] York and Lancaster Regiment

[5] York and Lancaster Regiment

[6] "The War Against Japan, Volume III, The Decisive Battles", Woodburn Kirby S., H.M.S.O. (1961)

[7] York and Lancaster Regiment; War diary 150th Regiment, R.A.C., WO 172/4601; WO 172/4602

[8] York and Lancaster Regiment; WO 172/4601; WO 172/4602

[9] The War Against Japan

[10] “At the Sharp End, From Le Paradis to Kohima”, Hart P. Pen & Sword (1998

[11] WO 172/4601; WO 172/4602

[12] WO 172/4601; WO 172/4602

[13] WO 172/4601; WO 172/4602

[14] York and Lancaster Regiment; WO 172/4601; WO 172/4602

[15] York and Lancaster Regiment; War diary 150th Regiment, R.A.C., WO 172/7345

[16] Marrison family

[17] Official History of the Indian Armed Forces in the Second World War, 1939-45; Reconquest of Burma, Volume II", Prasad N., Orient Longmans (1959)

[18] War diary 254th Indian Tank Brigade, WO 172/7142

[19] Marrison family

[20] “The History of The Welch Regiment, 1919-1951”, C. E. N. Lomax, John De Courcy, Western Mail & Echo Limited (1952); War diary 150th Regiment, R.A.C., WO 172/7345

[21] Marrison family

[22] WO 172/7345

[23] Marrison family

[24] Commonwealth War Graves Commission

[25] History of The Welch Regiment; WO 172/7345

[26] “The Worcestershire Regiment, 1922-1950”, Birdwood, Gale & Polden (1952); “Official History of the Indian Armed Forces in the Second World War, 1939-45, Reconquest of Burma, Vol II”, Prasad B., Orient Longmans (1959); “The War Against Japan Vol IV, The Reconquest of Burma”, Woodburn-Kirby S., HMSO (1956).

[27] Marrison family