Personal Account of Lt. Colonel Oscar Hugh Molloy

1st H.A.A. Battery, R.A., Burma Auxiliary Force

Oscar Hugh Molloy, born on 15th May 1941, served in Burma in both

civilian and military capacities from 1939 until 1946.

He was educated at St. Joeseph’s College, North Point,

Darjeeling and Rangoon University. His career

began with appointment to the Burma Civil Service (Class I) on

probation from 30th September 1938. His first

role was as an Assistant Commissioner, followed by promotion to

Senior District Officer for Meiktila. In November

1940, he volunteered for the Army, entering the Burma Auxiliary

Force and competing his basic training with the Militia at Maymyo.

Between 19th January and 10th May 1941, he underwent

anti-aircraft gunnery training in Singapore.

Upon his return to Burma, he joined the 1st Heavy Anti-Aircraft

Battery, R.A., Burma Auxiliary Force, one of two batteries of the

1st H.A.A. Regiment, R.A., B.A.F. He was granted

an Emergency Commission as Second Lieutenant on 16th October 1941

and appointed as Section Commander in charge of two 3.7-inch heavy

anti-aircraft guns. With the Battery, he took

part in the defence of Rangoon and in the subsequent retreat to

India.

He remained on the Burma Auxiliary Force reserve until later in

1942 when he was seconded to the Frontier Administration under H.Q.

IV Corps, serving in the Fort Hertz area at Sumprabum and Putao.

In February 1942 he was recalled to military service, most likely

being commissioned into the Army in Burma Reserve of Officers, and

posted to the Civil Affairs Service (Burma). He

continued to serve in North Burma as a Senior Civil Affairs Officer

and, later, District Civil Affairs Officer where he gave support to

the Americans and in turn received much support from them – quite

literally in the form of air-dropped supplies. By

1943 he had been promoted to Major, serving as a temporary Lt.

Colonel. He returned to India in April 1945

before being posted back to Burma; first at Minbu and then Tavoy,

where he became District Commissioner in 1946, before taking up the

D.C. role at Thayetmyo. He left the Service on

1st January 1946 on proceeding on leave prior to release.

He subsequently noted down his personal reminisences of his time with the 1st H.A.A. Battery, B.A.F. He descibes: training in Singapore; the defence of Rangoon; the withdrawal from the city; the retreat to India. A transcription of these notes is published below with the kind permission of the family.

Personal Account of Lt. Colonel Oscar Hugh Molloy

1st H.A.A. Battery, R.A., Burma Auxiliary Force

April 1941- June/July 1942

1) Infantry training:

1 month Maymyo – April 1941

2) Anti-aircraft training: 3 months

Singapore – April, May, June 1941

3) Stand by Rangoon: till

Dec 7, 1941 – Pearl Harbour

4) 1st Burma Campaign: and retreat to India

Maymyo – the usual routine as a Private; P.E., Arms

Drill, Marches, Bren Gun; Had done all this at

North Point and found

it boring and hoped to be sent soon to the O.T.C. – Officers

Training Corps. But, one morning, on parade, the

Captain i/c [in charge] our group said, “Those whose names I call

on, two steps forward, fall out and follow me.”

My name on the list and about six of us were told we’d been selected

for ack-ack training at Singapore, no nonsense, no argument and off

we go.

Off we went – two port officers, B.C.S.I. [Burma Civil Service

Grade I] (Gracie and I), four English civilians, business people,

salesmen. And have I learnt discrimination:

Gracie B.C.S.I. for five years, O.H. [Oscar Hugh – the author]

B.G.S.I. for one year. Gracie went as Staff

Sergeant; I as Gunner! Why? I

imagine because I was a local boy. The English

lads went as Bombardiers or Sergeants, and we had one who went as

“Major Jackson” (had spent time experience in the 25-pounders where

I had met him in the 1929/30/31 days).

Singapore – Aug(?) 1941

Rangoon - Singapore by tramp steamer – the Major (Jackson);

Gracie, Staff Sergeant; Robert Walker, Sergeant; David Brown,

Sergeant; Bobbie Carlton; Bombardier; Shorty –(?), Bombardier (a

Scot); good cabins or bunks; O.H. and the rest, some thirty odd,

down in the hot hot hold, surrounded by dust and merchandise; above

all, Jackson every day and all day, Parades, drill, P.E., lectures,

polished boots and buttons: four days of misery and hell to Penang

Island, two days rest and by train to Singapore, off to gun site on

the island just near the Causeway, Jorhat.

Instructors

Captain Helliwell, theory of ack-ack; shells, fuses,

ballistics; predictions by flight, expert on how to

use the Predictor and read out proper fuse and when to “Fire”.

Lectures every day.

Sergeant Macdonald, expert on drill, ordinary and gun drill;

setting fuse automatically or by hand; moving barrel smoothly up and

around (vertical and horizontal), levelling gun platform, loading

etc. etc. – very interesting indeed.

Sergeant Bailey; expert on range and height finder.

Major Jackson – an amateur but determined to show off. His

main job was discipline and running the camp; chores – the

cook-house, latrines, keeping the barracks cleaning [sic],

i/c Guard House duties (two hours on – four hours off, for two days

at a time) and he was always on the prowl (minute late and he’d play

hell! “Stop! – Who goes there?” “Gunner

Ispahani!” – “Password!” – “Bully beef!” “ Advance to be

recognised!” – “ Pass Gunner Ispahani”.

Guard duty was tiring – you felt worn out on duty and for the

next two days; and to me, all this “Stop – who goes there!” etc. was

a farce. The Jap enemy would have had a bullet or

a bayonet into you as soon as you opened your mouth! However,

“Jacko” loved spit and polish.

The Course We

all had to learn every job in the gun section; every number on the

gun, sergeant i/c gun crew, fuse setter, shell loader, operators to

move gun left/right, to elevate the barrel and lower (keeping arrows

in line); compass.

Predictor (4), setting height and angles, smoothly

following fuse(?) and height lines, following enemy planes.

Height Finder getting on to

leading plane, getting two images to become one, holding this steady

and following the plane.

I remember what we had to do. I enjoyed this

part of the course – it was something positive and the more you used

your head and were calm and collected, the easier and the more

satisfying. I think we all had to learn the job

of the Section Commander – all the routine, all the orders.

Sergeant Mac and Sergeant Bailey were very pleased with us,

arranged a shootout against the British and Indian 3-inch [gun]; we

had 3.7-inch. (told us not to bother about Jacko

as one of them would act as Section Commander).

We scored four out of six, British three out of six and Indians one

out of six; quite a noise in Ack Ack Singapore.

Singapore & Life

We had leave once a week – full army dress, always had to carry

“first aid” against gonorrhoea etc. or we’d be in the glass house if

M.P. checked and we’d forgotten it! And the

saluting – full of Officers. The Aussies wouldn’t

salute and called their officers by Christian name!

Sergeant Mac shook me – marched me to Red Light Balthasar Road

[Balestier Road?], up and down with him, patting the women (of all

nationalities – Asia and Europe) on their buttocks, thighs, stomach,

breasts (“I like to know what I’m buying!”). I’d

have to hang about until he had had his fling. He

told me frankly that many like him had to have a woman at least once

a week. Four/six women, of all ages and sizes,

out in front gardens near the gates, being inspected like cattle or

sheep in a pen – it was degrading but it was lucrative – throngs of

clients, English, Scotch, Welsh, Aussies, Indians, Chinese, Malays,

all walking about openly and examining. When they

had done, off they’d go to the nearest Red Light clinic for

treatment. I had to go to see, I saw; what I saw

sickened me and I never went again. But I had

learnt what some, it seemed, had to do.

Amusement Parks – Malayan boxing and dancing and music.

I liked and watched and even danced – you never held your partner

in an embrace, only swayed and moved opposite her.

Food – ate a lot of Chinese and Malayan food.

Raffles Hotel – actually went there with Gracie and his

wife. On my won, as a mere gunner, I could not

enter!

The real training course was finished in 6/8 weeks, we had to

take some sort of exams, written, oral and in charge of guns,

predictors etc., had to know the drill off by heart – and some were

rewarded by promotion. Gunner Molloy became

Serjeant Instructor etc. Our return to Burma was

held up because our guns had not arrived. But we

returned finally, and from the start, were on Red Alert!

(We all knew war was coming.)

Red Alert

a) two gun sections of two guns apiece to guard the Burma Oil

Refinery and tanks outside Rangoon – digging slit trenches, barb

wire, siting our guns, loading them up, unloading for two full hot

days stack boxes of shells (two to a box), heavy as the Devil,

drilling and training near gun crews, barrack room chores, guard

duty, latrine duty. As Sergeant Instructor I had

both physical and official jobs – digging, wiring, drawing up

rosters of duty and leave, ordering rations, checking barracks and

medic [sic], falling in morning parades, reporting to Section

commander, getting orders and having really to do all the training.

Walker and Brown now Lieutenant and 2nd Lieutenant fully

dressed, officer’s hats and canes, Sam Brownes etc. mainly

supervised; very aloof they were and aped Jacko in his attitudes and

obeyances to the letter of King’s Regs. Carlton,

also with us and a 2nd Lieutenant, was the only human one – said to

me he felt such a fool, ordering me about and being saluted by me

and being reported to by me.

[I] remember marching across paddy/rice fields full of water and

mud, cobras and krites [kraits] and others watching us as we marched

on a compass straight line, setting up new target area for when the

crop had been reaped, about Sept/Oct? Not one

snake attacked, they looked, we looked and stayed still, we

both said “Hello, no harm meant!” and off they swam to another place

and we walked on. Lesson – don’t put a snake in

danger and it’ll push off; it knows it can’t eat you.

And so time passed and we were moved to Rangoon itself: Indian

3-inch Ack Ack [3rd L.A.A. Battery, Indian Artillery] took over the

oil refinery and tanks and we, 1st Regiment Royal Artillery Heavy

A.A. [1st H.A.A. Regiment, R.A., B.A.F.], had to start afresh on the

East Bank of the Rangoon River – all the chores to be done again.

But this time, I was a 2nd Lieutenant and Section Commander with

two mobile guns of my own. Not that Jacko

promoted me – the man had a fixation about me all the time.

My Promotion

In July/August/September, John was posted to the Secretariat, Rgn

(Rangoon), together with other Senior Officers of the Burma Frontier

Service – object being to plan for Kachins, Karens, Chins etc. To be

recruited into special forces to fight Japs in the Hill Tracts.

Naturally, I marched in, Serjeant Instructor: Iris very

pleased and proud of her sergeant brother, John fuming and saying

the B.C.S. [Burma Civil Service] had more need of me than the Army

had of a Sergeant; Breakey [sic] wanted me back and so on and on.

Could even find me a job elsewhere – to Hell with the Army if

they valued me only as a sergeant.

So, Chief Sec. spoken to, Gov[ernor] spoken and Govt. told Army

“If Govt. Officers, B.C.S.I were not good enough to be given a

commissioned rank, dismiss them at once – we could make good use of

them – so, Army H.Q. saw to it that all B.C.S.I people like me were

promoted. Jacko snarled and took it out on me –

constant surprise visits, even at nights, not enough discipline with

my men, mustn’t eat or drink with them, more gun drill, I hadn’t a

clue of camouflage guns “You should see how well Walker has done

about this!”, couldn’t cope, Molloy, with a night exercise – three

minutes late at rendezvous, four minutes late on drill, would have

to put in adverse report. I could have slain him.

But we carried on and thank God, Henderson from U.K. Ack Ack

(Chief Instructor, Captain/Major) told us our drill was good and up

to scratch and told me not to let Jacko get me down.

But I know that until my section provided themselves in

action, Jacko could criticise and we had to grin and bear it – we

were hopeless, Walker and Brown were tops. He

really persecuted us during Red Alert – night drills, telephone

drill at night and leave practically nil.

The reason was – I, a local lad, was B.C.S.I and if he had come

to me in my civilian capacity, he would have had to say “Sir” to me;

he couldn’t join my clubs as of right and in the social hierarchy,

he was very much my inferior. A very small mind.

Action December 7th 1941, Pearl

Harbour and we were at war with Japan.

December 1941 – March 1942: action in Rangoon, till the retreat

December 23rd – Japs came twice in broad daylight, up the river

over Rangoon.

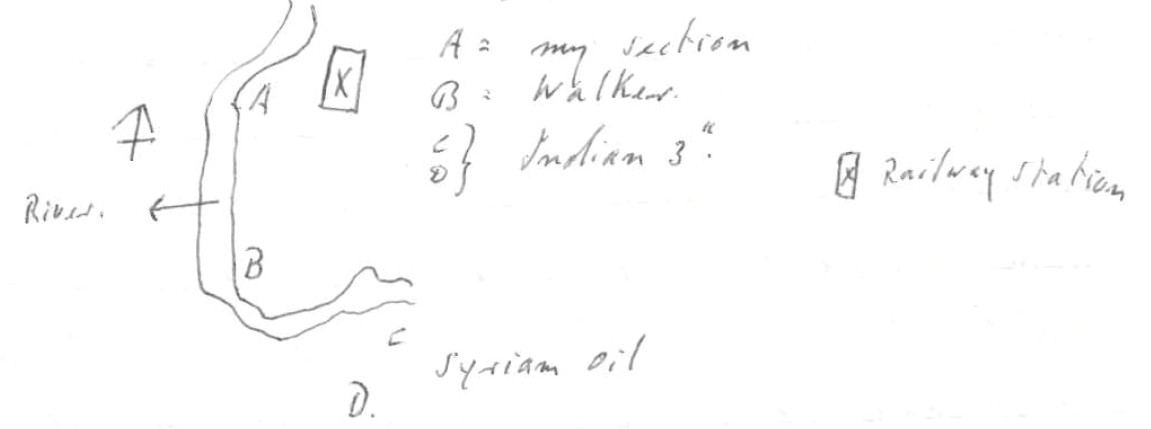

Ahlone Period

I must confess when I saw through my special telescope the Rising

Sun I was shocked and scared but routine and drill paid off – C and

D [see map above] went into action and when the Japs were in range A

went into action. Walker ordered “Take cover,

slit trenches!” – not around was fired by him.

We fired six shells, three per gun, only as the Japs took

avoiding action but we brought down six planes in all, the only

planes shot down that engagement. We knocked down

another three of the second flight an hour later – Japs flew the

same formation, the same route.

Henderson rang at once, “Good show!” and came as soon as he could

to compliment all of us and to question and to quiz - why had A

Section done so well – B, C, D, nil. We,

Sergeants, men and myself gave all the details he wanted for

analysis – Jacko came late afternoon and said “Beginners Luck!” – we

said “Maybe!”.

December 25th Christmas – 2nd Bombing of Rangoon

(the town not the docks, or installations; just the houses.

I knew that this time they’d come with the sun in the East or in

the West, difficult to see and when the alarm went about 3pm we

peered into the sun, dark glasses and all; and they came.

We barely saw them but we had time to get on to them, open

fire and the bombs fell in the river, on the railway station and

outside the site. We saw them coming down just

that one raid, seemingly directed at A Section.

As I told Henderson, camouflage was nonsense – one shell fired by us

and we were pin-pointed, out on the riverbank on a curve, railway

station close to us. And so it was.

At this site, Ahlone, we saw action quite a lot but only to keep

the Japs away from the airfield, didn’t bomb Rangoon again.

Nights – damn nuisance up for quite a spell, heard the Japs.

No searchlights at all and all we could do was aim at where we

guessed the planes would be. May have damaged but

we saw no crashes; except once, when a single Jap flew slowly and

steadily low down with all his lights on, wings and cabin.

The men said, “Let’s have a go, Sir! What

does the bastard think he’s up to!”

I told the men it was dangerous – the pale moon was shining, the

river gleamed, the Jap observer would be watching and we could see

only the lights – difficult to do what was needed but we’d have a go

if all did their jobs quietly and slowly and with care – the Jap was

cruising along. I made the height finder fix on

the red wing light, took six heights and stood by the predictor with

the fuse drums; it seemed to take ages to get a regular reading, but

we set the fuse and I watched and waited till the arrows went

smoothly and the gun sergeants said they were ready and smooth, I

prayed a small prayer and “Fire!”. If we missed,

the gun flashes would pin point us, the Jap, not far way and low

down (two miles) would douse lights and down he’d come and bomb –

but the men did as they promised and in that cold darkish night they

were perfect – quite commands, quiet drill, quiet confidence, our

shells (two only) burst bright and we saw the Jap plane lit up

clearly, wings, cabin, fuselage, I swear I saw the men inside, the

lights went out, the sound of the engines changed and three-five

minutes later we heard a crash and the explosion.

We had a drink and I reported a hit – Henderson said he had been

watching and was positive we had a hit; Jacko came next day and

said, “Nonsense! That kind of shooting couldn’t

be accepted.” But the same evening, the Headman’s

reports came in, the Army went out and found the plane and dead Japs

and the gashes and rents and burns caused by shell bursts and parts

of our shells buried in the engine and frame.

Jacko, “Lucky once again, Molloy, isn’t your Section?!”.

Lesson if the Ahlone Period

Respect and trust your men, drill properly, confide in them,

create confidence and team spirit, don’t use rank, be firm but just

and you’ve made a team. Discuss and talk with

them and if you’re going to take a risk, take a calculated risk

after full explanation. Jacko, once we’d had our

successes at Ahlone kept away for the most part.

I think Henderson told Section A was bloody good, he’d better be

occupied with Section B and their lack of success – not a plane, not

a barrage at night and not a plane at night.

Static 3.7-inch gun site

At Ahlone, couldn’t move the guns but when you had levelled them

properly, you could swing them round and round with a push from a

finger. I loved them but I had them for one/two

weeks. Bobby Carlton took over after we had done all the donkey work

– Jacko’s pet and persecution.

Mingladon Aerodrome Period – Rangoon, R.A.F. and

U.S.A. Tigers – Tomahawks

Japs determined to bomb aerodrome and destroy R.A.F. and U.S.A.

who were really volunteers (Chenault’s) came from China – all their

planes’ fronts were painted as sharks gaping mouths; they were mad

but damned good fighter pilots.

Memories of this site

a) Not enough sandbags for protection; every time we fired clouds

of dust

b) Rangoon a dead town, looted; we got American heavy trucks to

haul our mobile 3.7-inch [guns]; our Scammels handed to Tank Corps.

Had to go down to the docks, grab the trucks, pinch petrol

drums, drive off. It was absolute chaos.

Sent men out to get transport – grabbed two German cars,

small ones, took Doctor’s Bag of tricks (instruments) and medical

supplies left behind (drugs, syringes, knives, the whole lot),

destroyed what I thought we’d not need. We were

preparing for the evacuation of Rangoon – my section was!

Sergeant Ispahani – height finder expert – had a very bad

tooth, out it had to come, no Army dentist anywhere; so O.H. used a

“freezing” aerosol, a pair of pliers, commonsense, and out came the

tooth. Section A was out on its own and on a limb

so we organised ourselves – transport (private) pinched, petrol

drums filled from local garages or abandoned cars, food in tins and

cans from stores abandoned – chickens, ducks, meat – if people sold,

we paid; if people had left, we took the abandoned chickens and

tins.

c) Action – quite successful if Japs came our way; bombs and

fighters against the airfield. Bombers were easy

meat; they flew like robots and if they were in range we always

knocked three/five down; even fighter bombers flew like robots –

dead straight, fixed speed and we’d take them on, bring down

two/three and the rest would turn tail and go home, quite a few

billowing smoke; these we could not claim.

Section A was still good – Burmans, Indians, Anglo-Burmans,

Anglo-Indians; not one man from the West.

We had quite a lot of form(?) – the Japs outnumbered the R.A.F.

and the Tigers, two to one; and we’d see a Tiger havering off,

chased by a Jap; so we’d go into action. Good

drill, good judgement and we’d put two shells between Tiger and Jap,

and the Jap fighter would pull out and punch out.

We had a few “Thank you’s” from the Tigers. We

were really good; I say it and I know it.

But, although Section A did its job and prepared for the evacuation,

we felt hemmed in – the men felt their wives were out on a limb, no

money getting to them from the Pay Corps, anxious, depressed.

I know what it was like – had not seen Iris and John since

November 1941, nor Mother nor Mary since December 29th (in a bomb

shelter near the Rangoon football ground!).

So, I said to my men – “If all of you deserted tomorrow and went

off to find wife and children, I cannot really blames you.

We know, things being what they are, you could easily go to

ground and be lost for ever. I can’t stop you and

I won’t stop you – go and find your family, get your money troubles

straightened out, and come back. I need a

fighting Section A; pared to the bone – I’ll cook and wash up if

need be – but to keep us as a fighting unit, we’ll have to have a

roster of who goes and when. So, we’ll draw cards

and off you go – four/five/six days, see you family, arrange things

and back you come; the next one goes. But,

back you come; if you’re afraid to come back, send me word, I’ll

have you posted as “deserter”, but don’t bother, because we’ll never

catch you!”. Remember, Section A is very special

– we are the best in the whole of the Ack Ack in Burma.

And so my men went off – Absent Without Leave – A.W.O.L. – but

they came back, and right to the end they lived and fought and died

with me. It was difficult but I always had a full

section for fighting – if necessary, I’d cook and wash – we all

mucked in.

d) Jacko again – the man was an ass.

The Tigers and R.A.F. had phoned the Colonel to ask them to thank

Section A for their accurate shooting, day and night.

So down came Jacko to find out: he found a fighting unit, but

no spares – “Where are the missing men?” – Jacko.

O.H. “Finding families, getting money”.

Jacko “They’re deserters. I’ll court martial

them!”

O.H. “Don’t think about King’s Regs. I decided

to do this my way; Section A will always be a fighting unit; but I

must let every man be quite of mind.”

Naturally he reported me to the Colonel, naturally I had to

appear – thank God that Henderson and the U.S. Tigers thought so

highly of Section A. Also, General Alexander,

C-in-C., had visited Section A and we had told him we were fed up

with the Pay Corps handling of family payments and that it might

lead to A.W.O.L., not desertions – no doubt he had spoken to the

Colonel.

But Jacko had to have his dig. Watched me

doing the usual gun drill, called the Sergeants in charge and me to

a meeting, and said everything was wrong and he couldn’t but believe

our record of planes was but luck. He would do

the gun drill and line up with the guns. He took

over, gave the orders and did the lining up – I called the men to

fall in, told them I disagreed and that if the Japs attacked us we’d

be shooting wild; told Jacko that as Section commander I would

insist on Henderson checking what had been done.

Jacko fumed but I had the right and on the spot ‘phoned Henderson.

Jacko went off in a temper, Henderson came down, checked what

Jacko had done and blew his top. We did the

correct drill, Henderson phoned H.Q. and ordered Jacko to meet him

and told the Col[onel] that never again was Jacko to interfere with

Section A’s gun drill. I was told later that he

played hell with Jacko and told him to get off our backs, that we

know our job damned sight better than he ever would.

From then on, Jacko never interfered with any gun drill – he

became purely administrative.

Last Days in Rangoon

The Colonel took me out of Section A into H.Q. – a liaison job

for him and all the sections, heavy A.A. and Bofors , maybe because

I knew my job, maybe because he knew that one day there’d be hell to

play [sic] if Jackon interfered with Section A.

The only part of this job I enjoyed was visiting the gun sites

and trying to help on the usual problems – but the prissiness and

regimentation of H.Q., starchy talk, pompous meals and so on turned

my stomach. I spent as much time as I could in

the Sergeants’ Mess and learnt a lot about the logistics of a war –

rations, supplies of arms, ammo, pay, medic etc.: the Sergeants

carried the whole Regiment. And from them, I got

the real truth as to what was happening.

Breaking out of Rangoon

Had to visit each gun section with orders; when to move out;

which routes to take, where to meet and how to hide under trees etc.

– we were evacuating Rangoon. H.Q. moved out but

I had a roving commission; on the move all the time on my own,

checking on movements of Sections and finally, at the end of the

day, seeing them bedded down and fed. The next

day we and the whole of the Army in Rangoon were supposed to move

out but late in the evening we were told stay “put” – Japs had cut

the road. And so, off to tell the Sections, then

to drive into the “blockade” zone to find out what the hell was

going on: tanks, Armoured Corps, Gurkhas, the whole damn lot – tanks

blazing, rifles blazing, saw lots of Japs (Tied to tree branches)

quite dead, a few still firing away. Wonder how

many 1000’s rounds were fired into treetops.

Funny I felt no fear or danger – I and my driver in my looted Opel

merely wandered about, shoo’d by M.P.s, told to get out of the

bloody way, got first hand info, sent the driver back to Colonel,

wandered about and returned on foot. (I have no imagination.)

As a matter for fact, the Jap force holding us up was about a

battalion, their Army corps gone far too West and we got out because

of the Jap’s mistake. On the way to Prome and

Tharrawaddy – still with H.q., still haring up and down in contact

with Heavy guns and Bofors while H.Q. and Jacko motored on and

settled down to pink gins and whisky! Jap

fighters swoop down on the road, stop the car, into the ditch and

hope for the best. Two/three days of this bloody

boring work – but we all got through. What I

hated was having to be in H.Q. Mess every night; except for

Henderson. He told me that our Regiment, and my

Section A especially, were damned site better Ack Ack than the best

in England – I said, “The job I’m doing can be done by any clerk,

any dog’s body; I want to be with my men. Get me

out!”.

For about four/five [days] after we broke out of Rangoon, I was

still the liaison officer, inspecting gun sites and seeing to the

Bofors – action with them once, defending a bridge with little

cover.

Bobby Carlton had taken over Section A; some Jap Zeroes came

swopping down and things appeared to get out of hand, three men

wounded, one with his liver badly. The men blamed

Bobby for bad orders and wrong fuse setting and said they had no

confidence in him. So, Henderson had me sent back

as Section Commander. From now, Tharrawaddy,

Prome, Meiktila, Mandalay, Sagaing, Monywa, Kalemyo and Kalewa, it

was a question of being on the move – never more than two/three days

at a place.

Highlights

Prome: digging and filling sandbags in

the heat of the day and someone says, “Oscar Molloy, stop digging

and come”. I look up and it’s Richard Marsh, my

football captain at Jesus College, Oxford! Now a

2nd Lieutenant in [the] King’s Own Yorkshire [Light Infantry].

We went into action about three times a day and each time we

fired, the gun blast blew clouds of dust all around it and it is a

wonder that the Japs didn’t bomb us or shoot us up.

Aerodrome and bridge duty was dangerous.

Meiktila: My home town; got leave to find nanny and my

Kyaw who had looked after me and the home where I was first in

Meiktila but couldn’t find them. On my return,

found the Japs had bombed heavily and one man, not on duty, had his

head cut off because he would stand out in the open watching the

action.

Mandalay: As we were driving en route,

Sergeant Godenho comes and tells me that the Jap radio had said that

as soon as we, and Section A, had got to Mandalay, they’d bomb us to

hell -even gave the approximate time and quite a few of our names.

We decided to make haste, no stopping and got into Mandalay,

chose our site and broke records getting ready; everyone got

cracking. And two/three minutes after we were

ready, the Japs came – ever since we had left Rangoon, the only

warning we had was hearing the planes; six small bombers making for

us (their intelligence must have been good). But

we had time enough to get on to them and blew three of them out of

the sky and their bombs came nowhere.

That night about 8pm fires started near our site – left a guard,

all the rest off to beat out the fire and as we went we fired bursts

of Bren gun and shouted, “Everyone out of the fire sone; if you stay

you might die!”. It was eerie; flames and smoke,

buildings collapsing, people running and we trying to prevent the

flames getting to our ammo and equipment.

I heard Gerald was at Maymyo and got leave to find him; did so;

returned with food and strawberries and veg.

I didn’t know why but Henderson came to take over as Section

Commander; told me that H.Q. had ordered we go to Lashio and make

our way into China; destroy the guns etc. of the roads were too bad.

This was bad news – the Chinese Border roads were very bad

and none of us wanted to be anywhere near the Chinese “bandits” and

only obeying Chiang Kai-Shek.

Fortunately, we were told to get to Sagaing, cross the bridge and

protect it. On the way to Sagaing, Henderson left

us, never saw him again. And I took over. Jacko

appeared, positioned us in a stupid position and we stayed on until

the whole damned Army was across. Naturally we

had a hectic time, raids all the time, but we had Indian and British

A.A. as well and the bridge was not bombed. We

watched the sappers bomb it and off we went late about 4pm to

Monywa.

At Sagaing, we had to put on gas masks to bury seven corpses near

our site – killed by bombs and full of maggots and decaying flesh.

Arrived in Monywa in the dark, town in flames and roads bombed;

M.P.s very very good in navigating us to the gun site.

Pale moonlight and odd shapes all around us – in the morning

5am we saw they were cattle, all dead, on their backs, all legs

stiff and pointing to the heavens. One idiot used

his Tommy Gun; the explosions and smell were horrible.

Monywa had a small airfield and we had the usual raids, stayed

about two/three days and then moved west towards the River Chindwin

and the villages of Kalemyo and Kalewa on the banks.

When we were about fifteen miles away, we were told to

abandon guns, destroy firing pins and expose ammo to the sun and get

rid of fuse caps – the guns were too heavy to be ferried across but

we could have helped to defend the ferry crossing.

Instead, we had to hand over our transport so that the tanks

and Armoured Brigade could be taken to India – their tanks couldn’t

be ferried.

From now on we walked and slept on the hard rice fields and the

A.A> unit was split up; we were on our own, “Make your way up the

Kabaw Valley and into India!”. For a day or two

Jacko tagged on to us – no more being the Jacko, but asking our help

for scrounging food and water and living on the jungle.

Rations issued – one tin bully beef for two for four days; hard

dry biscuits, ten cigarettes, one water bottle full, “It’ll have to

do!”. Digging in dry streams and collecting

water, collecting water from the radiators of shot up and abandoned

trucks, scrounging food from the civilian refugees who had lots and

lots and were willing to share.

The Kabaw Valley March Out

All our H.Q. Staff disappeared after the river crossing – presume

they had been given transport. We just marched on

– scrounging, begging, get roots and fruit from the jungle, men

footsore and many with blisters whom we had to carry on improvised

stretchers – and all the time, Indian Army supply trucks returning

empty from the river ferry would not stop and give us a lift.

One day a Jeep stopped alongside and in it was General

Alexander – “I know your face; 3.7-inch mobile guns at Mingaladon.”

“Yes, Sir, you inspected my section.”

“Yes, yes, where is your transport?” “Handed over

to Armoured Brigade.” “Ah well, but can we help?”

“Yes, Sir, tell the Indian Army Supply Corps to pick up

troops walking up into India – we are getting fed [up?] – see trucks

loaded with fridges, pianos, furniture; drivers of empty trucks

refuse to take us unless we pay and God knows we’ve not had pay for

weeks. One day we’ll shoot the drivers and

commandeer the trucks. We’ve been marching for

eight days on practically empty stomachs and empty water bottles and

these trucks returning empty embitters us.”

Alexander was one of the best commanders in the Army

(Montgomery’s c-in-c later on) always spick and span, but a humane

soldier. He didn’t preach at us, no platitudes,

but ordered, on the spot, that a senior British Officer be sent down

the line to make sure returning trucks did not carry things of no

use and were to pick up all troops on foot.

24

December 2025